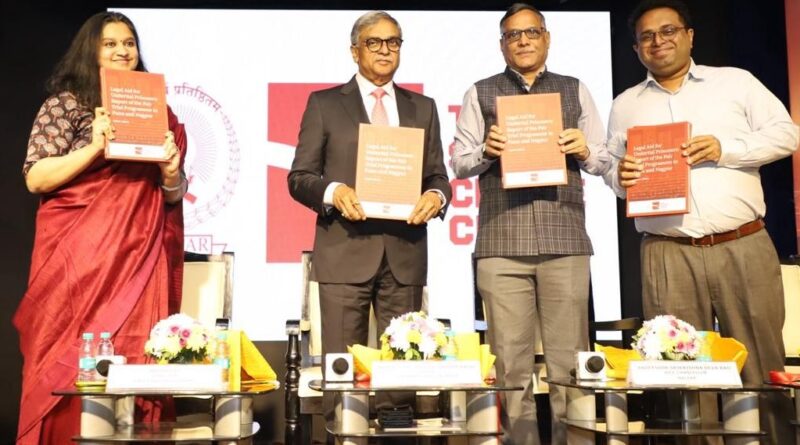

Justice Vikram Nath: India’s Prisons Filled with 70% ‘Legally Innocent’ Awaiting Trial

Access to this exclusive content is available only to our subscribers

Annual Subscription

₹ 820/year

(Plus ₹ 180 GST)

SUBSCRIBE NOWWith your support, we are able to provide an extensive range of content to you at an accessible subscription model